Sunday, December 13, 2009

#8-- NO MORE SHALL WE PART

With legacy acts like this, the watershed moment usually comes fairly early on in their career: yes, Morrissey's still making records, but it's not like there's been any revelations since The Queen is Dead. With Cave, however, it's hard to even identify a singular watershed. 1988's Tender Prey epitomizes the darker, grinding side of Cave's work, 96's Murder Ballads his pitch-black senses of humor and narrative.

2001's No More Shall We Part--released after a 4-year hiatus, following the bleak, naked apocalypse of The Boatman's Call--is Cave at his most mature, most emotionally powerful, and the height of his songwriting talent. There's nothing on here to match the brutal sexuality of "Deanna" or the horror of "Song of Joy," but the incredible love and loss throughout it is astonishing. After twenty-five years of hard work as a songwriter, Cave finally wrote the album he was born to.

The whole thing is wintery, melancholy. It's not a sad album--there's moments of incredible tender love, and sly comedy in "God Is In The House." It's an album of post-desolation, though, of quiet recovery, an album made of slight smiles and gentle touches. There are only a few times that it really cuts loose (helped greatly by the contributions of Warren Ellis on his banshee violin), and the quietude of the album empowers them to unbelievable heights.

Moreso than anything, however, Cave's lyrics shine. From the sarcastic exultation to "get down on our knees and very quietly shout: 'hallelujah'" to the cheerfully bitter poetry of "Darker With the Day" ("a steeple tore the stomach from a lonely little cloud"), No More Shall We Part stands as one of the incredibly rare albums that could almost be read, which could stand on its own as a work of poetry.

Friday, December 11, 2009

#9-- FEVER TO TELL

The influences are clear: the Siouxsie Sioux wail, the Stooge-y clang and grind, Telelvision's pairing of virtuosity and grit, Kathleen Hannah's massive lady-balls, Chrissie Hynde's imperiousness. None of that detracts from the album, however-- O, Zinner, and Chase are one of those rare musical groups (see also: Gnarls Barkley, Jack White) that are able to compress 30 years of musical legacy into a unique sound.

That compression, actually, is what makes this such an amazing album. The whole thing feels perfectly trimmed, as sparse as a skeleton, like something made out of copper wire and hot glue. It never really slows, it never lets go, and every single song is absurdly hook-laden and perfectly performed. It actually makes a pretty perfect companion to the Violent Femmes' first album in that regard: it's rickety, bare frame hides an incredible amount of venom.

Karen O may draw the most attention, but it has to be said: Nick Zinner is probably the best guitarist of modern rock. He blends showy brilliance with an incredible ability to create a wall of sound and pretty incredible songwriting chops. And Brian Chase ain't no slouch neither.

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

TOP 10 ALBUMS OF THE DECADE-- #10

Labor Days is a phenomenal album. Seriously, as in the literal sense. Eight years later it's still Aes's definitive work, and the album that symbolizes Def Jux and their fellow travelers.

It also, like the nine on my list that'll follow from here until the beginning of the twenty-teens, represents something about modern music to me, represents some of what this decade is made of sonically. The incredible denseness, the sneer, the sparsity. The album was released just a week after 9/11 and, while the event itself isn't reflected directly, Labor Days fits snugly into the post-WTC modern paranoia, the Raskolnikovian sense of malaise that's characterized the past ten years.

The album itself, recorded while Aesop was still working full-time, is a cynical dismemberment of modern urbanism-- fast food, wage slavery, soot, dying dreams, the 9-5 trudge. Firmly grounded in Rock's own Brooklyn, it flutters back and forth from the manic to the depressive, from skies to subways. It's Aesop's darkest, as well-- psychically violent, sooty, despairing. Aesop's sense of humor is subdued here, manifesting primarily as sarcasm.

Finally, Labor Days is a meaningful album. One of the veins that runs through hip-hop is that of class, wealth, and disparity, and Aesop speaks to that better than any other musician I've heard. My good friend Solomon credits it with pushing him into a new phase of his life, and it's hard to deny the potential power of the work.

And that's why Labor Days is ranked #10 on my list-- it's powerful, perfectly constructed, and succeeds on every level it approaches.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Let my mouth be ever fresh with praise.

Haven't updated since the end of summer--busy with school--but come on: new Mountain Goats album. You KNOW I'm not gonna pass that up.

For starters, let me just recommend Bible Gateway; it's gonna be a huge help. Because, just like he did sometimes in his tapedeck-and-yelling days, Darnielle's named some of the tracks on The Life of the World to Come after bible verses. All of the tracks.

I'm not really gonna harp on the premise too much--sometimes it helps lend some extra depth to the songs, sometimes it doesn't--but I will say that it provides a nice backdrop to the album. Whereas Heretic Pride seemed to revolve around heresy, people finding their own faiths, and its motley cure of individuals seemed the usual Mountain Goats crew of disparate misfits, The Life of the World to Come revolves around faith, belief, the role that religion plays in our lives. From the desperate tweaker faith of "Psalms 40 and 2" (He has fixed his sign in the sky! He has raised me from the pit, AND HE WILL SET ME HIGH!), to the simple faith in love in "Genesis 30:3", it's an album about finding comfort, about human warmth, about the redemptive powers of belief.

(May I also say that "Genesis 30:3" has in it a line that ranks alongside the climax of "Going to Georgia"--"the most remarkable thing about you standing in the doorway is that it's you--and that you're standing in the doorway."--for a bluntly simple, still-beautiful declaration of love? I think I can. "I will do what you ask me to/because of how I feel about you.")

The album is most reminiscent, not of Heretic Pride, but of Satanic Messiah, last year's EP (have you heard it yet? Oh man, it's so good. It's free!), which was also a series of toned-down, piano-centric songs about religion and faith. This may be it's greatest weakness, however: while Satanic Messiah is one of Darnielle's strongest efforts ever, it's also only 4 songs long. The melancholy sweetness starts to drag a bit on the full album; "Psalms 40 and 2" is the most energetic song by a mile, and in a way I'm reminded of Bright Eye's Cassadaga--"it's great and all, but would you mind screaming a bit more?" The Life of the World to Come needs a bit more energy to it, is all.

Which isn't to say that there's not some really beautiful stuff in the quiet bits. "Ezekiel 7 and the Permanent Efficiacy of Grace" stands alongside "Your Belgian Things" and "Maybe Sprout Wings" as one of the most affecting, stingingly sad songs Darnielle's ever written. The most powerful moment on the album, in fact, comes when you realize why its drug-addicted narrator is making a run for the Mexican border, in the two lines that come out of nowhere as a confession before he returns to his plan. Similarly, "Matthew 25:21", about watching his mother-in-law die of cancer, deserves the slow, tired pace. However, I wish that there were more songs like "Romans 10:9", a joyous exaltation of the power of God in providing stability in an unstable life, a rolling, exuberant song containing probably the best line in the whole album: "won't take the medication but it's good to have around/a kind and loving god won't let my small ship run aground."

Musically, the album holds up well, although it seems like a step backwards from Heretic Pride--the instrumentation is less varied, and there's nothing as exciting and unexpected as the vicious guitars on "Lovecraft in Brooklyn" or the painful build-up of "In the Craters on the Moon." Life seems a little too under-produced, a little too simple, like a return to the Tallahassee era. (It's also Darnielle's first hi-fi album with Vanderslice nowhere on board, which is probably part of it).

Musically, the album holds up well, although it seems like a step backwards from Heretic Pride--the instrumentation is less varied, and there's nothing as exciting and unexpected as the vicious guitars on "Lovecraft in Brooklyn" or the painful build-up of "In the Craters on the Moon." Life seems a little too under-produced, a little too simple, like a return to the Tallahassee era. (It's also Darnielle's first hi-fi album with Vanderslice nowhere on board, which is probably part of it).All in all, it stands as a solid contribution, although not one of the Goats' strongest. Still though, Tallahassee and Get Lonely are both rock-solid albums as well, and Life is about as good as them. And when it shines, oh Lord, does it shine: "Ezekiel 7" is one of those songs you want to never end.

Watch: "Ezekiel 7 and the Permanent Efficiacy of Grace"

Download: "Genesis 3:23"

(Art: Caravaggio, Blake)

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

I was held up at yesterday's parties. I was needed in a conga line.

The album that I just can’t get out of my head as a comparison is Echo & The Bunnymen’s masterpiece Ocean Rain, in which another similarly discordant and theatrical band seemed not so much to settle down as to focus. There’s the same kind of simmering intensity between the two albums—while Krug refrains from showing off his grasp of words here as much as is normally his wont, lines like “tell the new kids where I hid the wine / tell their fathers that I’m on their way” have a power and complexity that resonates—and the fact that Dragonslayer is an album draped in shimmery guitars, watery pianos, and creaking sighs doesn’t hurt the comparison. The most similar strain between the two, however, seems to be their ambition: like McCulloch before him (and unlike McCulloch’s happy-to-stagnate rival Bono—after reading one recent column in The Guardian I’ve been dying to take sides in that music-fan feud), Krug seems here to be reaching, not necessarily for new heights—the direction this album takes him is backwards from the bigger-louder-grander design of RSL—but towards new expanses, if not towards creating something bigger then to something deeper.

(Let me take a moment to say that, despite some similarities and a similar scheme, the Bunnymen aren’t the only comparison to draw. The usual culprits of Bowie and barrett pop up, the clatter and screech of “Black Swan” sounds more like Bauhaus than any modern goth band ever has, “Nightingale/December Song” has the rhythm and build of a Leonard Cohen song, and the quieter moments like the opening of “Dragon’s Lair” feel like snippets from Automatic For The People II: Moonman Boogaloo.)

The ambition doesn’t always pan out, of course, or there wouldn’t have been a need for Krug to release three albums this year. “Apollo and the Buffalo and Anna Anna Anna Oh!” is one of Krug’s stumbles—in addition to a title copped from the Sufjan Stevens School of Annoying and Impossible to Remember Song Titles (or Westward Ho! Young Man, said My Father), the lyrics don’t really hold together into a cohesive form. Several other songs have a similar failing, where they’re jam-packed with clever turns of phrase and powerful metaphors (“He would like to come home naked without whore-paint on his face / and appear before you virgin-white if virgins are still chaste”), it’s often hard to divine entirely what Krug is driving at. Dragonslayer never quite coalesces into the musical and thematic whole that the ragged and brash Shut Up or the intricate, operatic Random did—while “You Go On Ahead,” “Nightingale/December Song,” and “Silver Moons” are among the best songs that Krug has ever written, it’s hard to find the album itself as absorbing an experience as his previous two (well, previous two with this band; it holds up perfectly well next to Wolf Parade’s Apologies to the Queen Mary or Swan Lake’s Beast Moans). Still, though, Dragonslayer marks an exciting step towards maturity for Krug: like Lifted or The Rise and fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, it marks an artist on the verge of ascendance. Krug may still be sharpening his sword in this album, but it marks, hopefully, the first of several steps the prodigious young man may be taking towards the eventual Low or I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, and it’s certainly got me excited for the day when he finally slays that dragon.

Thursday, July 16, 2009

Is Control controlled by Its need to control?

Death is the seed from which I grow.

I will admit it, Burroughs is my favorite Beat. Kerouac has a beautiful, lackadaisical melancholy to him, Ginsberg resonates with the nerves and shaking coils of the cosmos (or at least he did for a staggeringly brief period between 1950 and 1960), but William S. more than any of them accomplished that most lofty of Beat ideals, the complete disposal of the corpse of language by acid-bath and its replacement with a doppelganger who, despite a strong resemblance to the poor victim, is fundamentally wrong on some level.

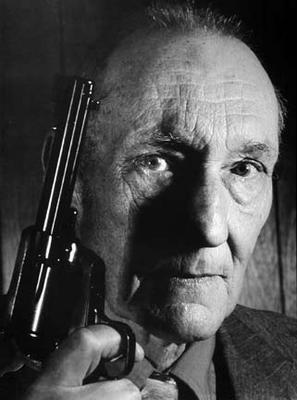

Right: Burroughs and oh my god why do people still let him have GUNS?

I read Naked Lunch when all red-blooded men should, my first year at college. It was gripping, fascinating, beautifully vulgar and disgusting and adventurous, although Burroughs' own personal obsessions-- predominantly underage gay sex --occasionally veer from interesting to obnoxious in their frequency. I read snippets of Ah Pook in high school, and thought that it wasn't that great; the meditations on death and life and Mayan myth were interesting enough, but I wasn't prepared for the lack of narrative drive. I read Junky at the same time and agree with Harvey Pekar's assertion that it holds up amazingly well; it's not Burroughs at his incendiary, obscene brilliance, but it's a fantastic portrait of his times and habits. And then in quick succession earlier this year I saw Cronenberg's Naked Lunch movie (a wonderfully incisive look into the mental Interzone that Burroughs inhabited while writing his most famous work, and the man who plays Ginsberg is dead-on prfect) and read Graham Caveney's Gentleman Junkie (which is not especially deep but is a beautifully-made book, and the fact that Chapter 5 has its margins lined with handguns is wonderful), and they both rekindled my interest in the man.

I recently started rereading Naked Lunch, and am reminded that I had forgotten the incredible amount of fun it is. The sardonic, faux-noir opening (I am evidently his idea of a character is a wonderful line), the boiling down of of Burroughs' spiritual war and the forces that surround him into the corporate competition of Interzone, Islam Inc., and Annexia, and the simple joy with words that pervades it (other smells curled through pink convolutions, touching unknown doors proves that, while he may have talked about smashing, dissasembling, and assassinating the English language, Burroughs knew how to use it)-- there's a sense of adventure and fun here that shows that, dspite his dark and nihilistic focus, Burroughs' dispostion never differed too much from Jack or Allen.

He may have been the most sinister (especially in Tangiers) of the three, but there's a sense of hope to his work at well, an exubeant freedom and revelment in the depths of it. Naked Lunch doesn't attempt a revolution, it's a missive from the already-freed lands, showing the rest of us how good it can be without those pesky laws or human decency. This isn't to say that it's a friendly book-- Cronenberg commented that a literal film adaptation would be banned in every country --but it's not a scream of loathing or rage a la Irvine Welsh (nothing against Mr. Welsh, as he may rank below Alasdair Gray as Scotland's foremost modern literary talent). Burroughs didn't trangress the laws so mch as he transmigrated into a world where they no longer existed, or transfigured them into something that would no longer apply to him. If the driving spirit of the Beat movement can be called freedom or, more stuffily, the assertion of the inividual, then it's Bill Burroughs, Junkie, Queer, and wife-killer, who it seems found it in its purest form

Tuesday, July 7, 2009

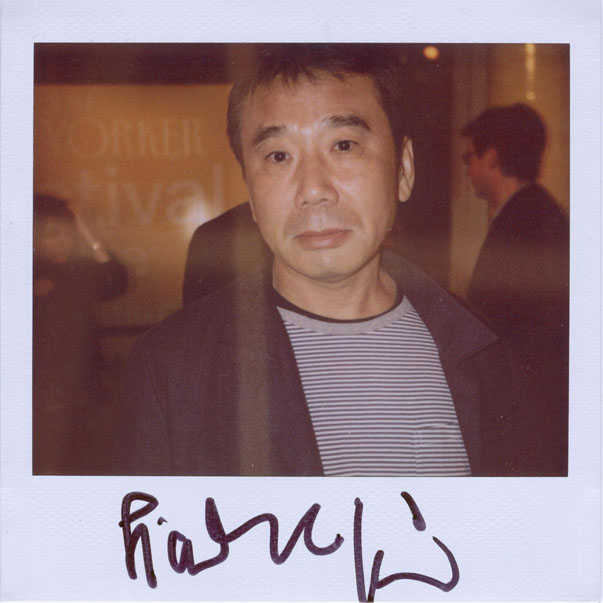

What Makes Haruki Murakami Special

I read Murakami's Kafka on the Shore very shortly after it came out, in one blast over a few summer days, spending hours in bed engrossed in it. And, when I've tried to explain why I love his works, it's difficult. It's not like Faulkner, where I can point to his intricate eloquence and complex moral subjects, or Vollmann, where I can point to his...intricate eloquence and complex moral subjects (I have a type, I know. I also like Dostoevsky). There's a charming simplicity to Murakami's langage (I assume, at least, having only read translations), but not a noticeable simplicity, a la Cormac McCarthy or Hemmingway. Murakami writes as though he does not think about writing, having only a story to lay out and ome interesting ideas, not all of which need to connect or make sense. He writes as though writing is a simple pleasure rather than a passion, but with a skill, tightness, and sense of construction that can only come from years of refinement.

Linguistically, in fact, his closest cousin seems to be the ever-wonderful Philip K. Dick, who is also the first writer whose work ever excited me on a literary level. Dick never concerned himself too much with the beauties of language, in part because Dick never considered himself more than a pulp writer. But the sparsity of Dick's prose has a complexity all of its own, freeing the ideas of the work to stand as the driving force, allowing the language to drape over them effortlessly so that the story moves at the pace it decides. And, like with Dick, this straightforwardness removes the illusion of a filter, making you feel, not like an audience, but like a guest in someone else's world. Good in both cases, because Dick was a schizophrenic and Murakami, divorced though he may be from the traditional demographic, impedes heavily into the territoy of magical realism; a plot involving Colonel Sanders as a Shinto pimp, an unidentified giant white slug, Johnny Walker killing cats to make a flute from their souls, a double-Oedipal curse, and Beethoven is hard enough to connect in outline form.

But what sets Murakami apart from the writers above, and from many of the modern Japanese canon (the genius, but perpetually dour Kenzuburo Oe comes to mind, as does the doomed fascist Mishima) is his incredible sense of whimsy and fun. Kafka is a charming novel, it that few of its riddles have solutions and never pretends to offer up a definite, great truth. It suggests at them-- the characters' conversations about Eichmann, Haydn, and eel all stand as wonderful examinations of ideas-- but it's a book whose rambling, tangled story and symbols are more fun than profound. I think that the village towards the end of the book represents a partial afterlife where the permanently damaged parts of people go to die, I think that recovery and redemption are major plot points, but, unlike Faulkner, I don't have to know. Murakami is a writer who, like Vonnegut, manages to be incredibly affecting and stirring without the need for grandiosity, whose works are both incredibly smart and incredibly fun. He creates worlds that obey their own logic, and it is clear that, while there are rules and laws, we will never know all of them. And, as a tourist in his world, maybe we'll have more fun if we don't.

Read: Haruki Murakami: On seeing the 100% perfect girl one beautiful April morning

2 Albums That Rocked my Damn Socks two years ago (pt. 2)

But where this is heading is that I spent a couple years of my life listening to bands that tried desperately hard to push the envelope of rock and roll as far as they could, and Sunset Rubdown’s Random Spirit Lover blows them out of the water with an unbelievably casual grace and natural flair.

There’s a lot of influences swirling around inside this album, so, to try and give a general overview: The Cure comes to mind when Spencer Krug belts and yelps, there’s a lot of “Ashes to Ashes”-era Bowie in the beeping, discordant instrumentation, an Echo and the Bunnymen-style grandiosity and melodrama, a definite infusion of Barrett-era Pink Floyd in the music’s chaos and clang, and there’s King Crimson’s theatricality. And that’s just musically; the album is an intricate and intensely symbolic coming-of-age story that feels like a collaboration between James Joyce and Guillermo Del Toro.

Lyrically, Spencer Krug is one of those unbearable geniuses who is both a show-off and so incredibly talented that you know he deserves to show off. When, in “Magic vs. Midas,” the central character of the album experiences the first blush of sexuality, Krug’s line of “you drew up a list of your luckiest stars, as you made me familiar to you in the dark” manages to both make its subject incredibly clear and be a delightfully difficult turn of phrase to unpack. And when he raises the issue of trust, asking “Hey you with the gold, which you keep (or which keeps you) in place. Do you recoil from its jail house green and copper taste?...Was it magic or Midas that touched you? And by magic I mean trickery. And by Midas I mean faith,” there’s brilliance in both the essential metaphor, exploring the question of whether one of the figures in the song is knowingly buying into a false love, and in the sly, sarcastic way he seems to take the listener aside to explain it to them in the final two sentences.

The album is full of these little moments, the incredibly complex knots of words buried under the soaring keyboards and rattling guitars. When, under the wall of xylophones and sing-songy rhythm of “Up On Your Leopard, Upon the End Of Your Feral Days,” Krug chants that “You’re the one who ran in the wild, ‘cause you’re the one the wild called,” the repetitive simplicity of the lyrics paired with the insistent, driving melody from a perfect portrait of the need for youthful exuberance. In “For the Pier (and Dead Shimmering),” one of several songs that starts off quiet (incredibly quiet—just gentle chimes and Krug’s stammering whisper), when the narrator desperately tries to reassure himself that this terrifying plunge into adulthood is natural, Krug’s voice builds from a whisper to an operatic scream as he madly reassures himself that “it’s the reining and the predatory nature of the sky, and the ringing sound it makes as it’s burning out your eyes. It’s all right. It’s all right. It’s the speed of light and the speed of a year.” And in “The Taming of the Hands That Came Back to Life,” a song that explores that oh-so-lovely feeling of “I’m twenty years old, why am I still desperate and confused?,” the pounding, unrelenting drums couple with Krug’s gentle vocals for a truly chilling moment when the narrator simply does not get someone else’s problems, so completely engrossed is he in his creative works:

She said “My sails are flapping in the wind.”

I said “Can I use that in a song?”

She said “I mean the end begins!”

I said “I know… Can I use that too?”

Of course, the album’s climax occurs in the most intricate song of all, the sarcastic and clever “Trumpet Trumpet, Toot Toot!,” a song layered with more walls of sound than anything on the album so far, and ghostly wooing female vocals snaking through the whole piece. Krug finally drops the mask of his varied characters, admitting that he is a player in the work as well, though coyly asking you to figure out “Was I the leopard? Or the virgin? Or the child in a grown man’s beard, all out of place and hanging off his face by the time the audience cheered?”

Of course, the album’s climax occurs in the most intricate song of all, the sarcastic and clever “Trumpet Trumpet, Toot Toot!,” a song layered with more walls of sound than anything on the album so far, and ghostly wooing female vocals snaking through the whole piece. Krug finally drops the mask of his varied characters, admitting that he is a player in the work as well, though coyly asking you to figure out “Was I the leopard? Or the virgin? Or the child in a grown man’s beard, all out of place and hanging off his face by the time the audience cheered?”

If the album has any fault, it’s that it’s too complex: clocking in at well over an hour, it can be exhausting to follow all the way through, and it’s really easy to skip some of the middle tracks to get to the album’s finish. But it fits the cocky, eloquent nature of the lyrics and theme—it’s like how Tesla would only give speeches in front of a running Tesla coil, shooting sparks around the room, just to show that he could. And Krug himself recognizes this, asking at the album’s close: “why so many, many, many, violins?”

Monday, July 6, 2009

2 Albums That Rocked my Damn Socks two years ago (pt. 1)

The charming fellow above is mister Jaime Meline, alias El Producto, alias El-P. Producer, CEO, sometimes jazz composer and, oh yeah, a rapper. And his 2007 album was a little blossom of pure darkness called I'll Sleep When You're Dead.

The charming fellow above is mister Jaime Meline, alias El Producto, alias El-P. Producer, CEO, sometimes jazz composer and, oh yeah, a rapper. And his 2007 album was a little blossom of pure darkness called I'll Sleep When You're Dead.Musically, the album is incredibly rich, in part thanks to the throng of cameo musicians: Cat Power's cooing hooks on "Poisenville Kids No Wins" are the most beautiful thing she's ever recorded, Camu Tao (RIP) provides a chilling vocal warble in the backbeat of "The Overly Dramatic Truth" that manages to steal the show from El's twisting lyrics of sexual regret, the Mars Volta and Trent Reznor lend touches that sound exactly like their work and fit seamlessly with El's glitchy, claustrophobic beats (did I mention he produced the entire album himself?), and the guest verse from Aesop Rock is absolutely fantastic ("three out of the five of these fuses are wired live, if I wanna survive I gotta FIND THOSE DETONATORS"). But El-P put his brain front and center here, and if the dude is gonna put himself on a slab you may as well examine it.

When the lead single from your album puts the star in Guantanamo and the opening lines of it are fell asleep late neon buzz, PTS Stress we do drugs you know it's not gonna be a happy little romp. Monsieur Producto has always been confrontational and paranoid-- his first album, Fantastic Damage, dealt with his sister's rape, his abusive stepfather, and his love of Orwell with an almost terrifying bluntness--I'll Sleep is a totally different beast. It's dark, broody, absolutely drenched in paranoia. El is a huge Philip K. Dick fan and it shows. "Habeas Corpses (Draconian Love)," El-P's homage to dystopian science fiction, is a perfect example: it follows two executioners (El-P and fellow Def Jukie Cage, pictured below with El in their allotted five minutes a day of Not Being Scary as Hell) on a prison ship full of political malcontents, and is unbearably chilling.

El-P: I'm saying during the tenure of your gig, have you ever heard of prisoner who, despite the traitorous label, makes you nervous as a kid? Who may be beyond a date with the lead, maybe there's something else meant for her? A prisoner with the beauty of prisoner 247290-Zed?

El-P: I'm saying during the tenure of your gig, have you ever heard of prisoner who, despite the traitorous label, makes you nervous as a kid? Who may be beyond a date with the lead, maybe there's something else meant for her? A prisoner with the beauty of prisoner 247290-Zed?Cage: Oh God, you gotta be joking, I get it she's smoking. Go get a taste, I'll hold you down for thirty, she must be purty or open. Your secret's safe with me, go on a raping spree. I gotta couple numbers of my own, just return the courtesy.

...Yeah. The world isn't just going to hell, but El-P freely admits to getting a sick thrill of the ride, or, as he bellows in the beginning of "Drive:" "Come on Ma, can I borrow the keys? My generation is carpoolin with DOOM and DISEASE!" From the purely political-- such as when he informs "Dear Sirs" that if "time flows in reverse, death becomes my birth, me fighting in your war is still, by a large margin, the least likely thing that will EVER FUCKING HAPPEN, EVER"--to the personal, such as when, in "League of Extraordinary Nobodies," he puts a laugh track to his life and admits that "I haven't even gotten to the part where it's a joke," the album is full of mistrust, paranoia, and a dark glee at the miserable fun of it all. Or, as "Smithereens" puts it, "why should I be sober when God is so clearly dusted out his mind?"

Why indeed, El?

Tune in next time to discover what the other absoltely killer album of 2007 was. Was it Sunset Rubdown's Random Spirit Lover? Yes. Yes it was.

Supermagic-blackalicious-Def-we-got-that-dopeness

While Kanye may claim to be the spokesperson of his (and my) generation—and, let’s be frank, this isn’t as ridiculous a claim as most people scoffed that it was; have you heard “Jesus Walks?” Is there any better song that manages to be that angry, introspective, and so damn catchy?--The Ecstatic ranks up there with El-P’s I’ll Sleep When You’re Dead and Bright Eyes’ I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning as one of the truest, clearest expressions of our modern age to ever be pressed onto vinyl. What it doesn’t have of those two (odd, considering the Boogieman’s momentary bouts of crazy) is the misery or real awful dreams about giant apocalyptic machinery just mowin’ us all down. The Ecstatic is, well, ecstatic, almost entirely free of the self-righteous anger that is one of Mos’s few failings as an MC.

Those who have listened to The New Danger will know his other main failing: Mos is just too damn clever for his own good. Yes Mos, we really admire your fusion of punk rock and hip-hop, but do we need three different tracks that explore it in the same manner? Your blues numbers are really great, but do they need to be six minutes long? And the last twenty minutes of that album have some pretty decent songs Mos, but seventy minutes is too long for a rap album.

The Ecstatic, on the other hand, is every bit as clever and innovative, but restrained. And, lyrically, it packs just as much of a punch as Def’s legendary debuts, Black Star and Black on Both Sides. Musically, it shines: from the El-P like doom and chitter of “Twilite Speedball” to his back-and-forth with Georgia Anne Muldrow on “Roses,” where his rapping flows in between her classic-style R&B, the album is incredibly sophisticated and musically innovative. And on the occasions like the beautiful end of "Pistola" or the All-Spanish, All-Crooning "No Hey Nada Mas," when Mos breaks into full-out song, he establishes himself as being in the Cee-Lo caliber of "rappers who could cut an incredible soul album."

And, as stated, it’s an album that is in an incredible product of its time: it’s filled with Arabic chanting and religious hymns, “gentlemen getting down on those Middle-Eastern instruments,” as Slick Rick puts it in his guest verse. It opens with a quote from Malcolm X, in the brief window between his view-altering pilgrimage and his incredibly suspicious death, and the sample that opens “The Embassy” is so bizarre, paranoia-inducing, and ominous that it, again, begs comparisons to El-P.

There’s an incredible element of hope throughout the album, however, something that was sorely lacking for many people in 2003 and 2007, when Cage and El-P, respectively, made the rap albums that best personified their times. Fitting enough, given that we no longer have a president who seems to view the entire world as our enemy. This is perhaps best exemplified by a line from “Wahid:” “Fret not ghetto world. Guess what: God is on your side. The devil is a lie. The Empire holds all the gold and the guns but when all is said and done there's only One.” Moreso than perhaps any Muslim rapper, Def has made an album fueled by his faith and the beliefs that lie at his very core. Interestingly, the album it calls to mind for me, more than any other, is Burning Spear’s Marcus Garvey, a similarly lush and experimental outpouring of faith, protest, hope, and beauty. And, like Marcus Garvey, one can only hope that The Ecstatic goes down, not simply as a career-defining album for Mos, but as an album that defines its medium in its age. Mos himself seems to recognize this album's importance as a potential icon, declaring in the lead single:

Tuesday, June 16, 2009

"I remember Donna as she was 3 months ago, and most faces get lost in the haze"

Purcell’s “Dido & Aeneas” at Sadlers Wells Theatre in London, 2007

Over at Last Plane to Jakarta, John Darnielle is saying that Blackout Beach's (solo project of Frog Eyes frontman Carey Mercer) Skin of Evil (does it get its name from the Star Trek episode? I would not be surprised!) is quite possibly the album of the year, at least so far (I've got high hopes for Sunset Rubdown's upcoming Dragonslayer, but I'd feel bad naming it the best album of the year considering that Random Spirit Lover was probably the best or second-best album of 2007). And I've been listening to this enigmatic, 30-minute bottle of smoke since it came out and I could not agree more.

First, to give a feel for the album's sound, Darnielle is right when he says that there is nothing that sounds quite like it: Mercer's usual flair for theatrical wailing and clattering is transformed here into a subtle, brooding, shifting work. It's still unsettling and off-putting, but in a dreadful, ominous way: it's the wailing of a single ghost in a haunted house, rather than the discordant shanty of a whole ship of the dead. Unlike his last solo effort though, the mostly uninteresting Light Flows the Putrid Dawn, Skin of Evil doesn't feel overly simplified or incomplete; Skin of Evil has an incredible number of layers, full of whispers, gentle hums, subdued keening, and Mercer's unmistakable wail loses none of its desperation when he quiets down.

And while there may be nothing else that sounds like it, here are five songs it instantly calls to mind, forming a pretty impressive pedigree of vaporous gloom:

1. David Bowie's "Always Crashing in the Same Car"

2. The Cure's "Plainsong"

3. Joy Division's "Day Of the Lords"

4. The Talking Heads' "Born Under Punches"

5. Echo and the Bunnymen's "All My Colours"

The lyrics, however, not only stand comparison by beg it. Mercer draws on a huge array of classical archetypes to paint a fractured, multi-viewer portrait of the imaginary Donna, a woman loved and feared and worshipped by the "soft men" who tell us their stories throughout the album. Donna is (in chronological order) Eve, Helen, Dido, Dante's Beatrice, Don Quixote's Desdamona, Shostakovich's Elena. And Mercer's lyrics can do "her" (for it is clear that Donna is not merely one woman, but all women worshipped by man, and so perhaps Desdamona is the best example, in that The essential point is that without seeing her [beauty] you must believe, confess, swear, and defend it,” as Quixote told his vanquished foes): "Donna takes her name from the beauty of the wintertime: the candied crust of the snow," he sings in the last song. Mercer, however, seems distinct from the narrators: he views both Donna and her pursuers with pity, feeling that, deep down, "the men just wanted to lay, just fall around the other and sift through the last dusty specks of the day. But," he says, knowing that his art depends on their striving towards a woman who would rather be alone, "I am evil, so I ordered them on! Company halt! I see Donna! I see her away!"

But the album is not Donna's portrait (nor is the woman on its cover, though the artwork is all manner of beautiful)-- we only once see her, as herself: on the shore of a cape town in winter, "huddled and wet and holding some cracked tape; it only played two songs." But neither Donna nor the narrator can discard the tape. This is the core of Mercer's album, of the recursive music that circles like a building funnel cloud around Donna herself, of the moans and woes of the men who haunt her; at it's base, it's about obsession and worship.

And, as the best damn music I've heard this year, it should inspire some of its own.

Give it a listen.

Monday, June 15, 2009

A Tale of the Black Freighter

"Pirate Jenny" is, like a vast array of other oft-covered songs ("Mack the Knife," "September Song," and "Alabama Song," among others), the work of German composer/songwriter Kurt Weill. And, like "Mack the Knife," it was written for his collaboration with postmodern playwright Bertolt Brecht, The Threepenny Opera (Die Dreigroschenoper)-- the barmaid Polly Peachum (no one knows why Polly- rather than the actual Jenny herself) is asked by the crew of thieves and thugs at her wedding reception to sing them a song, so she delivers a merry tune about murdering them all and razing the town.

"Pirate Jenny" is, like a vast array of other oft-covered songs ("Mack the Knife," "September Song," and "Alabama Song," among others), the work of German composer/songwriter Kurt Weill. And, like "Mack the Knife," it was written for his collaboration with postmodern playwright Bertolt Brecht, The Threepenny Opera (Die Dreigroschenoper)-- the barmaid Polly Peachum (no one knows why Polly- rather than the actual Jenny herself) is asked by the crew of thieves and thugs at her wedding reception to sing them a song, so she delivers a merry tune about murdering them all and razing the town.Pretty standard stuff for Brecht, honestly, and only slightly darker than the usual Weill fare.

What many, many people miss in their versions of "Pirate Jenny," as with a great deal of Weill's work (God bless you Bobby Darin, but Macheath is supposed to be a figure of irredeemible evil), is the seething emotional intensity that's supposed to be in it. Polly is a trod-upon figure: the daughter of a beggar-king, married in a stable to a murderer and rapist, competing romantically with a whore. Couple that with Brecht's hardcore communism and the fact that the "Beggar's Opera" is a seething attack on the crimes of all classes, and you can picture the boiling resentment that finally comes to a head in Polly's only solo song in the play.

What many, many people miss in their versions of "Pirate Jenny," as with a great deal of Weill's work (God bless you Bobby Darin, but Macheath is supposed to be a figure of irredeemible evil), is the seething emotional intensity that's supposed to be in it. Polly is a trod-upon figure: the daughter of a beggar-king, married in a stable to a murderer and rapist, competing romantically with a whore. Couple that with Brecht's hardcore communism and the fact that the "Beggar's Opera" is a seething attack on the crimes of all classes, and you can picture the boiling resentment that finally comes to a head in Polly's only solo song in the play.This is where Nina Simone, one of the greatest female black singers in history (and I would say the greatest, except that Billy has such incredible inertia behind her reputation), comes in with fists swinging. After all, it's not as though Bobby Darin knew oppression or poverty firsthand. But

"Pirate Jenny" seems to be a song tailor-made for, if not civil rights, then at least the angry masses. And whereas Brecht's original lyrics were written to resonate with the German underclass (which, in 1928, was pretty angry without his help), Simone makes no bones as to whom she speaks: there are only two major changes her version makes from the most common English translation (please, anyone but Blitzstein, Blitzstein who translated "Pimp's Ballad" as "Memories Tango").

"Pirate Jenny" seems to be a song tailor-made for, if not civil rights, then at least the angry masses. And whereas Brecht's original lyrics were written to resonate with the German underclass (which, in 1928, was pretty angry without his help), Simone makes no bones as to whom she speaks: there are only two major changes her version makes from the most common English translation (please, anyone but Blitzstein, Blitzstein who translated "Pimp's Ballad" as "Memories Tango").One is from "and you'll see me dressed in tatters in this ratty old hotel"to "in this crummy Southern town in this crummy old hotel," which does a huge amount to cement Simone's version as being sung, if not by her, then by someone of her background. The other, while more subtle,

packs an even stronger punch. Whereas the original German is simply "There's a ship in the harbor," Simone changes it to "there's a ship: the black freighter," bellowing out the line with what is quite possibly the voice of God; if you don't get a little shiver, then I as your friend take it as a responsibility to save you from the shambolic state of undeath you must be in. Sung by a black woman, in 1964, on the same album that included "Mississippi Goddam" there is little room for imagination as to what the freighter represents to Simone's narrator: we will come, we will destroy those who held us down, and I will be our queen.

packs an even stronger punch. Whereas the original German is simply "There's a ship in the harbor," Simone changes it to "there's a ship: the black freighter," bellowing out the line with what is quite possibly the voice of God; if you don't get a little shiver, then I as your friend take it as a responsibility to save you from the shambolic state of undeath you must be in. Sung by a black woman, in 1964, on the same album that included "Mississippi Goddam" there is little room for imagination as to what the freighter represents to Simone's narrator: we will come, we will destroy those who held us down, and I will be our queen.It's not all power politics in Simone's version though. Besides all that murderin' and pillagin,' there's a really strong sexual element that gets missed (although the '97 Donmar Warehouse recording of the play nails that hard, nails it like the play was Mack and the sexual element was any woman with a pulse). Simone taps into the sadism and t

he urge for power that is such a huge part of Polly's character. In the second-to-last verse, Simone trades her brimstone bellow for a nearly-orgasmic moan, following up her pleading, whimpering in the quiet of death with the incredibly tense, gasping right. now. To play the song straight would be ludicrous-- it's Brecht, the man who defined his style around "the distancing effect"--and Simone taps into its inherent cruelty, viciousness, and the power fantasy contained within it. It's nuanced, it's absolutely chilling, and it's one of Simone's absolute best performances. Just listen to it.

he urge for power that is such a huge part of Polly's character. In the second-to-last verse, Simone trades her brimstone bellow for a nearly-orgasmic moan, following up her pleading, whimpering in the quiet of death with the incredibly tense, gasping right. now. To play the song straight would be ludicrous-- it's Brecht, the man who defined his style around "the distancing effect"--and Simone taps into its inherent cruelty, viciousness, and the power fantasy contained within it. It's nuanced, it's absolutely chilling, and it's one of Simone's absolute best performances. Just listen to it.(The art at left certainly isn't conicidental-- Alan Moore admits that the Black Freighter story thread in Watchmen was inspired by Weill and Brecht's song, especially Simone's version).

Dang dogg but if it ain't been a long time

So first a real quick music round-up:

This has been one of my favorite videos for pretty much ever and stands as a good testament to why, exactly, John Darnielle commands a following only slightly less devoted than Haile Selassie (although waaaaay whiter).

Found this tune on Amazon earlier today, and it's definitely worth checking out. Very much in the Dresden Dolls / World/Inferno Friendship Society vein (though not as awesome as the latter), with a bit of that Tilly and the Wall Four-girls-shouting-in-unison sound. And it's free which, let's face it, should be the case with all absinthe-soaked cabaret guttersnapes.

And I'm just gonna put Shipping Up to Boston here because any day that doesn't include that isn't a real day.

Also, Pat Robertson is HELLA dumb. Ignoring the subtext of his statement-- that violently attacking someone who has deviant desires, whether they act on them or not, is somehow okay--you ever read much about a duck's genitals? To summarize Miriam Goldstein via Not David Attenbrough, "oh, EW! Ew ew ew ew ew ew. BARF!" This opinion...is BULLshit.

So that's it for now, but I'ma try to keep this regular for a while.