Nick Cave has been going the longest and the hardest of any of the musicians on this list--with the Bad Seeds since '81 and the Birthday Party since '76. Probably longer than any of the previously mentioned musicians have been alive.

With legacy acts like this, the watershed moment usually comes fairly early on in their career: yes, Morrissey's still making records, but it's not like there's been any revelations since The Queen is Dead. With Cave, however, it's hard to even identify a singular watershed. 1988's Tender Prey epitomizes the darker, grinding side of Cave's work, 96's Murder Ballads his pitch-black senses of humor and narrative.

2001's No More Shall We Part--released after a 4-year hiatus, following the bleak, naked apocalypse of The Boatman's Call--is Cave at his most mature, most emotionally powerful, and the height of his songwriting talent. There's nothing on here to match the brutal sexuality of "Deanna" or the horror of "Song of Joy," but the incredible love and loss throughout it is astonishing. After twenty-five years of hard work as a songwriter, Cave finally wrote the album he was born to.

The whole thing is wintery, melancholy. It's not a sad album--there's moments of incredible tender love, and sly comedy in "God Is In The House." It's an album of post-desolation, though, of quiet recovery, an album made of slight smiles and gentle touches. There are only a few times that it really cuts loose (helped greatly by the contributions of Warren Ellis on his banshee violin), and the quietude of the album empowers them to unbelievable heights.

Moreso than anything, however, Cave's lyrics shine. From the sarcastic exultation to "get down on our knees and very quietly shout: 'hallelujah'" to the cheerfully bitter poetry of "Darker With the Day" ("a steeple tore the stomach from a lonely little cloud"), No More Shall We Part stands as one of the incredibly rare albums that could almost be read, which could stand on its own as a work of poetry.

Sunday, December 13, 2009

Friday, December 11, 2009

#9-- FEVER TO TELL

When I was 16 I made a list of the best albums of this decade, SO FAR, and put the Yeah Yeah Yeah's Fever to Tell at the very top of it. Now, obviously, I've reconsidered since then, but very clearly not too much. It's still a great album, and still stands as the YYY's best work.

The influences are clear: the Siouxsie Sioux wail, the Stooge-y clang and grind, Telelvision's pairing of virtuosity and grit, Kathleen Hannah's massive lady-balls, Chrissie Hynde's imperiousness. None of that detracts from the album, however-- O, Zinner, and Chase are one of those rare musical groups (see also: Gnarls Barkley, Jack White) that are able to compress 30 years of musical legacy into a unique sound.

That compression, actually, is what makes this such an amazing album. The whole thing feels perfectly trimmed, as sparse as a skeleton, like something made out of copper wire and hot glue. It never really slows, it never lets go, and every single song is absurdly hook-laden and perfectly performed. It actually makes a pretty perfect companion to the Violent Femmes' first album in that regard: it's rickety, bare frame hides an incredible amount of venom.

Karen O may draw the most attention, but it has to be said: Nick Zinner is probably the best guitarist of modern rock. He blends showy brilliance with an incredible ability to create a wall of sound and pretty incredible songwriting chops. And Brian Chase ain't no slouch neither.

The influences are clear: the Siouxsie Sioux wail, the Stooge-y clang and grind, Telelvision's pairing of virtuosity and grit, Kathleen Hannah's massive lady-balls, Chrissie Hynde's imperiousness. None of that detracts from the album, however-- O, Zinner, and Chase are one of those rare musical groups (see also: Gnarls Barkley, Jack White) that are able to compress 30 years of musical legacy into a unique sound.

That compression, actually, is what makes this such an amazing album. The whole thing feels perfectly trimmed, as sparse as a skeleton, like something made out of copper wire and hot glue. It never really slows, it never lets go, and every single song is absurdly hook-laden and perfectly performed. It actually makes a pretty perfect companion to the Violent Femmes' first album in that regard: it's rickety, bare frame hides an incredible amount of venom.

Karen O may draw the most attention, but it has to be said: Nick Zinner is probably the best guitarist of modern rock. He blends showy brilliance with an incredible ability to create a wall of sound and pretty incredible songwriting chops. And Brian Chase ain't no slouch neither.

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

TOP 10 ALBUMS OF THE DECADE-- #10

AESOP ROCK-- LABOR DAYS

Labor Days is a phenomenal album. Seriously, as in the literal sense. Eight years later it's still Aes's definitive work, and the album that symbolizes Def Jux and their fellow travelers.

It also, like the nine on my list that'll follow from here until the beginning of the twenty-teens, represents something about modern music to me, represents some of what this decade is made of sonically. The incredible denseness, the sneer, the sparsity. The album was released just a week after 9/11 and, while the event itself isn't reflected directly, Labor Days fits snugly into the post-WTC modern paranoia, the Raskolnikovian sense of malaise that's characterized the past ten years.

The album itself, recorded while Aesop was still working full-time, is a cynical dismemberment of modern urbanism-- fast food, wage slavery, soot, dying dreams, the 9-5 trudge. Firmly grounded in Rock's own Brooklyn, it flutters back and forth from the manic to the depressive, from skies to subways. It's Aesop's darkest, as well-- psychically violent, sooty, despairing. Aesop's sense of humor is subdued here, manifesting primarily as sarcasm.

Finally, Labor Days is a meaningful album. One of the veins that runs through hip-hop is that of class, wealth, and disparity, and Aesop speaks to that better than any other musician I've heard. My good friend Solomon credits it with pushing him into a new phase of his life, and it's hard to deny the potential power of the work.

And that's why Labor Days is ranked #10 on my list-- it's powerful, perfectly constructed, and succeeds on every level it approaches.

Labor Days is a phenomenal album. Seriously, as in the literal sense. Eight years later it's still Aes's definitive work, and the album that symbolizes Def Jux and their fellow travelers.

It also, like the nine on my list that'll follow from here until the beginning of the twenty-teens, represents something about modern music to me, represents some of what this decade is made of sonically. The incredible denseness, the sneer, the sparsity. The album was released just a week after 9/11 and, while the event itself isn't reflected directly, Labor Days fits snugly into the post-WTC modern paranoia, the Raskolnikovian sense of malaise that's characterized the past ten years.

The album itself, recorded while Aesop was still working full-time, is a cynical dismemberment of modern urbanism-- fast food, wage slavery, soot, dying dreams, the 9-5 trudge. Firmly grounded in Rock's own Brooklyn, it flutters back and forth from the manic to the depressive, from skies to subways. It's Aesop's darkest, as well-- psychically violent, sooty, despairing. Aesop's sense of humor is subdued here, manifesting primarily as sarcasm.

Finally, Labor Days is a meaningful album. One of the veins that runs through hip-hop is that of class, wealth, and disparity, and Aesop speaks to that better than any other musician I've heard. My good friend Solomon credits it with pushing him into a new phase of his life, and it's hard to deny the potential power of the work.

And that's why Labor Days is ranked #10 on my list-- it's powerful, perfectly constructed, and succeeds on every level it approaches.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Let my mouth be ever fresh with praise.

Haven't updated since the end of summer--busy with school--but come on: new Mountain Goats album. You KNOW I'm not gonna pass that up.

For starters, let me just recommend Bible Gateway; it's gonna be a huge help. Because, just like he did sometimes in his tapedeck-and-yelling days, Darnielle's named some of the tracks on The Life of the World to Come after bible verses. All of the tracks.

I'm not really gonna harp on the premise too much--sometimes it helps lend some extra depth to the songs, sometimes it doesn't--but I will say that it provides a nice backdrop to the album. Whereas Heretic Pride seemed to revolve around heresy, people finding their own faiths, and its motley cure of individuals seemed the usual Mountain Goats crew of disparate misfits, The Life of the World to Come revolves around faith, belief, the role that religion plays in our lives. From the desperate tweaker faith of "Psalms 40 and 2" (He has fixed his sign in the sky! He has raised me from the pit, AND HE WILL SET ME HIGH!), to the simple faith in love in "Genesis 30:3", it's an album about finding comfort, about human warmth, about the redemptive powers of belief.

(May I also say that "Genesis 30:3" has in it a line that ranks alongside the climax of "Going to Georgia"--"the most remarkable thing about you standing in the doorway is that it's you--and that you're standing in the doorway."--for a bluntly simple, still-beautiful declaration of love? I think I can. "I will do what you ask me to/because of how I feel about you.")

The album is most reminiscent, not of Heretic Pride, but of Satanic Messiah, last year's EP (have you heard it yet? Oh man, it's so good. It's free!), which was also a series of toned-down, piano-centric songs about religion and faith. This may be it's greatest weakness, however: while Satanic Messiah is one of Darnielle's strongest efforts ever, it's also only 4 songs long. The melancholy sweetness starts to drag a bit on the full album; "Psalms 40 and 2" is the most energetic song by a mile, and in a way I'm reminded of Bright Eye's Cassadaga--"it's great and all, but would you mind screaming a bit more?" The Life of the World to Come needs a bit more energy to it, is all.

Which isn't to say that there's not some really beautiful stuff in the quiet bits. "Ezekiel 7 and the Permanent Efficiacy of Grace" stands alongside "Your Belgian Things" and "Maybe Sprout Wings" as one of the most affecting, stingingly sad songs Darnielle's ever written. The most powerful moment on the album, in fact, comes when you realize why its drug-addicted narrator is making a run for the Mexican border, in the two lines that come out of nowhere as a confession before he returns to his plan. Similarly, "Matthew 25:21", about watching his mother-in-law die of cancer, deserves the slow, tired pace. However, I wish that there were more songs like "Romans 10:9", a joyous exaltation of the power of God in providing stability in an unstable life, a rolling, exuberant song containing probably the best line in the whole album: "won't take the medication but it's good to have around/a kind and loving god won't let my small ship run aground."

Musically, the album holds up well, although it seems like a step backwards from Heretic Pride--the instrumentation is less varied, and there's nothing as exciting and unexpected as the vicious guitars on "Lovecraft in Brooklyn" or the painful build-up of "In the Craters on the Moon." Life seems a little too under-produced, a little too simple, like a return to the Tallahassee era. (It's also Darnielle's first hi-fi album with Vanderslice nowhere on board, which is probably part of it).

Musically, the album holds up well, although it seems like a step backwards from Heretic Pride--the instrumentation is less varied, and there's nothing as exciting and unexpected as the vicious guitars on "Lovecraft in Brooklyn" or the painful build-up of "In the Craters on the Moon." Life seems a little too under-produced, a little too simple, like a return to the Tallahassee era. (It's also Darnielle's first hi-fi album with Vanderslice nowhere on board, which is probably part of it).All in all, it stands as a solid contribution, although not one of the Goats' strongest. Still though, Tallahassee and Get Lonely are both rock-solid albums as well, and Life is about as good as them. And when it shines, oh Lord, does it shine: "Ezekiel 7" is one of those songs you want to never end.

Watch: "Ezekiel 7 and the Permanent Efficiacy of Grace"

Download: "Genesis 3:23"

(Art: Caravaggio, Blake)

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

I was held up at yesterday's parties. I was needed in a conga line.

Out of the five bands he’s performed in (the other four being straightforward alt-rockers Wolf Parade, should-be-more-amazing collaborative project Swan Lake, instrumental trio Fifths of Seven, and a now-over stint as the keyboardist for Frog Eyes), Spencer Krug’s work with Sunset Rubdown is undoubtedly the most personally driven. So when the first song on Dragonslayer is built around the chorus beginning with “I believe in growing old with grace” and the last around “It is time for a bigger kind of kill,” it’s hard not to apply those philosophies to the album itself. While it doesn’t have the brash, sledgehammer youthfulness of Shut Up I Am Dreaming or the sprawling grandiosity of Random Spirit Lover, the album still marks new evolutions in Krug’s style, not the least of which is a more mature, subtly constructed and meticulous sound. Krug’s signature yelp and holler is subdued here in favor of more whispers, feminine harmonies, and crooning, and it’s never sounded prettier. The wailing and clashing that marked his earlier albums is likewise turned down, with acoustic instruments finding more of a place here, although this is hardly an acoustic record.

The album that I just can’t get out of my head as a comparison is Echo & The Bunnymen’s masterpiece Ocean Rain, in which another similarly discordant and theatrical band seemed not so much to settle down as to focus. There’s the same kind of simmering intensity between the two albums—while Krug refrains from showing off his grasp of words here as much as is normally his wont, lines like “tell the new kids where I hid the wine / tell their fathers that I’m on their way” have a power and complexity that resonates—and the fact that Dragonslayer is an album draped in shimmery guitars, watery pianos, and creaking sighs doesn’t hurt the comparison. The most similar strain between the two, however, seems to be their ambition: like McCulloch before him (and unlike McCulloch’s happy-to-stagnate rival Bono—after reading one recent column in The Guardian I’ve been dying to take sides in that music-fan feud), Krug seems here to be reaching, not necessarily for new heights—the direction this album takes him is backwards from the bigger-louder-grander design of RSL—but towards new expanses, if not towards creating something bigger then to something deeper.

(Let me take a moment to say that, despite some similarities and a similar scheme, the Bunnymen aren’t the only comparison to draw. The usual culprits of Bowie and barrett pop up, the clatter and screech of “Black Swan” sounds more like Bauhaus than any modern goth band ever has, “Nightingale/December Song” has the rhythm and build of a Leonard Cohen song, and the quieter moments like the opening of “Dragon’s Lair” feel like snippets from Automatic For The People II: Moonman Boogaloo.)

The ambition doesn’t always pan out, of course, or there wouldn’t have been a need for Krug to release three albums this year. “Apollo and the Buffalo and Anna Anna Anna Oh!” is one of Krug’s stumbles—in addition to a title copped from the Sufjan Stevens School of Annoying and Impossible to Remember Song Titles (or Westward Ho! Young Man, said My Father), the lyrics don’t really hold together into a cohesive form. Several other songs have a similar failing, where they’re jam-packed with clever turns of phrase and powerful metaphors (“He would like to come home naked without whore-paint on his face / and appear before you virgin-white if virgins are still chaste”), it’s often hard to divine entirely what Krug is driving at. Dragonslayer never quite coalesces into the musical and thematic whole that the ragged and brash Shut Up or the intricate, operatic Random did—while “You Go On Ahead,” “Nightingale/December Song,” and “Silver Moons” are among the best songs that Krug has ever written, it’s hard to find the album itself as absorbing an experience as his previous two (well, previous two with this band; it holds up perfectly well next to Wolf Parade’s Apologies to the Queen Mary or Swan Lake’s Beast Moans). Still, though, Dragonslayer marks an exciting step towards maturity for Krug: like Lifted or The Rise and fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, it marks an artist on the verge of ascendance. Krug may still be sharpening his sword in this album, but it marks, hopefully, the first of several steps the prodigious young man may be taking towards the eventual Low or I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, and it’s certainly got me excited for the day when he finally slays that dragon.

The album that I just can’t get out of my head as a comparison is Echo & The Bunnymen’s masterpiece Ocean Rain, in which another similarly discordant and theatrical band seemed not so much to settle down as to focus. There’s the same kind of simmering intensity between the two albums—while Krug refrains from showing off his grasp of words here as much as is normally his wont, lines like “tell the new kids where I hid the wine / tell their fathers that I’m on their way” have a power and complexity that resonates—and the fact that Dragonslayer is an album draped in shimmery guitars, watery pianos, and creaking sighs doesn’t hurt the comparison. The most similar strain between the two, however, seems to be their ambition: like McCulloch before him (and unlike McCulloch’s happy-to-stagnate rival Bono—after reading one recent column in The Guardian I’ve been dying to take sides in that music-fan feud), Krug seems here to be reaching, not necessarily for new heights—the direction this album takes him is backwards from the bigger-louder-grander design of RSL—but towards new expanses, if not towards creating something bigger then to something deeper.

(Let me take a moment to say that, despite some similarities and a similar scheme, the Bunnymen aren’t the only comparison to draw. The usual culprits of Bowie and barrett pop up, the clatter and screech of “Black Swan” sounds more like Bauhaus than any modern goth band ever has, “Nightingale/December Song” has the rhythm and build of a Leonard Cohen song, and the quieter moments like the opening of “Dragon’s Lair” feel like snippets from Automatic For The People II: Moonman Boogaloo.)

The ambition doesn’t always pan out, of course, or there wouldn’t have been a need for Krug to release three albums this year. “Apollo and the Buffalo and Anna Anna Anna Oh!” is one of Krug’s stumbles—in addition to a title copped from the Sufjan Stevens School of Annoying and Impossible to Remember Song Titles (or Westward Ho! Young Man, said My Father), the lyrics don’t really hold together into a cohesive form. Several other songs have a similar failing, where they’re jam-packed with clever turns of phrase and powerful metaphors (“He would like to come home naked without whore-paint on his face / and appear before you virgin-white if virgins are still chaste”), it’s often hard to divine entirely what Krug is driving at. Dragonslayer never quite coalesces into the musical and thematic whole that the ragged and brash Shut Up or the intricate, operatic Random did—while “You Go On Ahead,” “Nightingale/December Song,” and “Silver Moons” are among the best songs that Krug has ever written, it’s hard to find the album itself as absorbing an experience as his previous two (well, previous two with this band; it holds up perfectly well next to Wolf Parade’s Apologies to the Queen Mary or Swan Lake’s Beast Moans). Still, though, Dragonslayer marks an exciting step towards maturity for Krug: like Lifted or The Rise and fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, it marks an artist on the verge of ascendance. Krug may still be sharpening his sword in this album, but it marks, hopefully, the first of several steps the prodigious young man may be taking towards the eventual Low or I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, and it’s certainly got me excited for the day when he finally slays that dragon.

Thursday, July 16, 2009

Is Control controlled by Its need to control?

Death is the seed from which I grow.

I will admit it, Burroughs is my favorite Beat. Kerouac has a beautiful, lackadaisical melancholy to him, Ginsberg resonates with the nerves and shaking coils of the cosmos (or at least he did for a staggeringly brief period between 1950 and 1960), but William S. more than any of them accomplished that most lofty of Beat ideals, the complete disposal of the corpse of language by acid-bath and its replacement with a doppelganger who, despite a strong resemblance to the poor victim, is fundamentally wrong on some level.

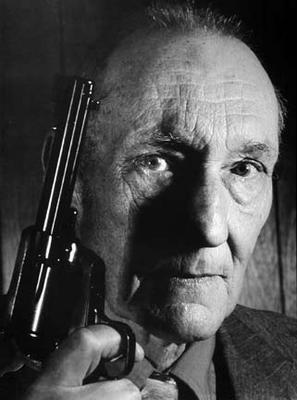

Right: Burroughs and oh my god why do people still let him have GUNS?

I read Naked Lunch when all red-blooded men should, my first year at college. It was gripping, fascinating, beautifully vulgar and disgusting and adventurous, although Burroughs' own personal obsessions-- predominantly underage gay sex --occasionally veer from interesting to obnoxious in their frequency. I read snippets of Ah Pook in high school, and thought that it wasn't that great; the meditations on death and life and Mayan myth were interesting enough, but I wasn't prepared for the lack of narrative drive. I read Junky at the same time and agree with Harvey Pekar's assertion that it holds up amazingly well; it's not Burroughs at his incendiary, obscene brilliance, but it's a fantastic portrait of his times and habits. And then in quick succession earlier this year I saw Cronenberg's Naked Lunch movie (a wonderfully incisive look into the mental Interzone that Burroughs inhabited while writing his most famous work, and the man who plays Ginsberg is dead-on prfect) and read Graham Caveney's Gentleman Junkie (which is not especially deep but is a beautifully-made book, and the fact that Chapter 5 has its margins lined with handguns is wonderful), and they both rekindled my interest in the man.

I recently started rereading Naked Lunch, and am reminded that I had forgotten the incredible amount of fun it is. The sardonic, faux-noir opening (I am evidently his idea of a character is a wonderful line), the boiling down of of Burroughs' spiritual war and the forces that surround him into the corporate competition of Interzone, Islam Inc., and Annexia, and the simple joy with words that pervades it (other smells curled through pink convolutions, touching unknown doors proves that, while he may have talked about smashing, dissasembling, and assassinating the English language, Burroughs knew how to use it)-- there's a sense of adventure and fun here that shows that, dspite his dark and nihilistic focus, Burroughs' dispostion never differed too much from Jack or Allen.

He may have been the most sinister (especially in Tangiers) of the three, but there's a sense of hope to his work at well, an exubeant freedom and revelment in the depths of it. Naked Lunch doesn't attempt a revolution, it's a missive from the already-freed lands, showing the rest of us how good it can be without those pesky laws or human decency. This isn't to say that it's a friendly book-- Cronenberg commented that a literal film adaptation would be banned in every country --but it's not a scream of loathing or rage a la Irvine Welsh (nothing against Mr. Welsh, as he may rank below Alasdair Gray as Scotland's foremost modern literary talent). Burroughs didn't trangress the laws so mch as he transmigrated into a world where they no longer existed, or transfigured them into something that would no longer apply to him. If the driving spirit of the Beat movement can be called freedom or, more stuffily, the assertion of the inividual, then it's Bill Burroughs, Junkie, Queer, and wife-killer, who it seems found it in its purest form

Tuesday, July 7, 2009

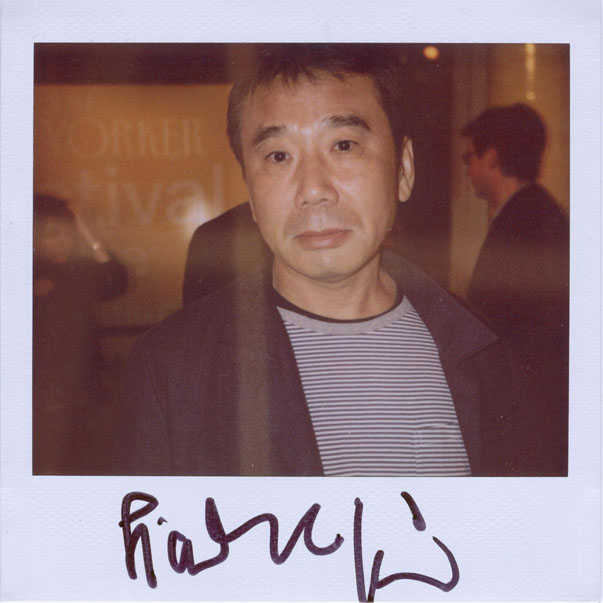

What Makes Haruki Murakami Special

I recently stated reading, intermittently, Haruki Murakami's Hard-Boiled Wonderland and The End of the World, mainly based on an article I read in The Writer's Chronicle about narrative paralellism and how the idea of two intersecting novels, one of which serves as an allegory for the workings of the other's protagonist's brain, sounded totally awesome. And I'm enjoying it so far.

I read Murakami's Kafka on the Shore very shortly after it came out, in one blast over a few summer days, spending hours in bed engrossed in it. And, when I've tried to explain why I love his works, it's difficult. It's not like Faulkner, where I can point to his intricate eloquence and complex moral subjects, or Vollmann, where I can point to his...intricate eloquence and complex moral subjects (I have a type, I know. I also like Dostoevsky). There's a charming simplicity to Murakami's langage (I assume, at least, having only read translations), but not a noticeable simplicity, a la Cormac McCarthy or Hemmingway. Murakami writes as though he does not think about writing, having only a story to lay out and ome interesting ideas, not all of which need to connect or make sense. He writes as though writing is a simple pleasure rather than a passion, but with a skill, tightness, and sense of construction that can only come from years of refinement.

Linguistically, in fact, his closest cousin seems to be the ever-wonderful Philip K. Dick, who is also the first writer whose work ever excited me on a literary level. Dick never concerned himself too much with the beauties of language, in part because Dick never considered himself more than a pulp writer. But the sparsity of Dick's prose has a complexity all of its own, freeing the ideas of the work to stand as the driving force, allowing the language to drape over them effortlessly so that the story moves at the pace it decides. And, like with Dick, this straightforwardness removes the illusion of a filter, making you feel, not like an audience, but like a guest in someone else's world. Good in both cases, because Dick was a schizophrenic and Murakami, divorced though he may be from the traditional demographic, impedes heavily into the territoy of magical realism; a plot involving Colonel Sanders as a Shinto pimp, an unidentified giant white slug, Johnny Walker killing cats to make a flute from their souls, a double-Oedipal curse, and Beethoven is hard enough to connect in outline form.

But what sets Murakami apart from the writers above, and from many of the modern Japanese canon (the genius, but perpetually dour Kenzuburo Oe comes to mind, as does the doomed fascist Mishima) is his incredible sense of whimsy and fun. Kafka is a charming novel, it that few of its riddles have solutions and never pretends to offer up a definite, great truth. It suggests at them-- the characters' conversations about Eichmann, Haydn, and eel all stand as wonderful examinations of ideas-- but it's a book whose rambling, tangled story and symbols are more fun than profound. I think that the village towards the end of the book represents a partial afterlife where the permanently damaged parts of people go to die, I think that recovery and redemption are major plot points, but, unlike Faulkner, I don't have to know. Murakami is a writer who, like Vonnegut, manages to be incredibly affecting and stirring without the need for grandiosity, whose works are both incredibly smart and incredibly fun. He creates worlds that obey their own logic, and it is clear that, while there are rules and laws, we will never know all of them. And, as a tourist in his world, maybe we'll have more fun if we don't.

Read: Haruki Murakami: On seeing the 100% perfect girl one beautiful April morning

I read Murakami's Kafka on the Shore very shortly after it came out, in one blast over a few summer days, spending hours in bed engrossed in it. And, when I've tried to explain why I love his works, it's difficult. It's not like Faulkner, where I can point to his intricate eloquence and complex moral subjects, or Vollmann, where I can point to his...intricate eloquence and complex moral subjects (I have a type, I know. I also like Dostoevsky). There's a charming simplicity to Murakami's langage (I assume, at least, having only read translations), but not a noticeable simplicity, a la Cormac McCarthy or Hemmingway. Murakami writes as though he does not think about writing, having only a story to lay out and ome interesting ideas, not all of which need to connect or make sense. He writes as though writing is a simple pleasure rather than a passion, but with a skill, tightness, and sense of construction that can only come from years of refinement.

Linguistically, in fact, his closest cousin seems to be the ever-wonderful Philip K. Dick, who is also the first writer whose work ever excited me on a literary level. Dick never concerned himself too much with the beauties of language, in part because Dick never considered himself more than a pulp writer. But the sparsity of Dick's prose has a complexity all of its own, freeing the ideas of the work to stand as the driving force, allowing the language to drape over them effortlessly so that the story moves at the pace it decides. And, like with Dick, this straightforwardness removes the illusion of a filter, making you feel, not like an audience, but like a guest in someone else's world. Good in both cases, because Dick was a schizophrenic and Murakami, divorced though he may be from the traditional demographic, impedes heavily into the territoy of magical realism; a plot involving Colonel Sanders as a Shinto pimp, an unidentified giant white slug, Johnny Walker killing cats to make a flute from their souls, a double-Oedipal curse, and Beethoven is hard enough to connect in outline form.

But what sets Murakami apart from the writers above, and from many of the modern Japanese canon (the genius, but perpetually dour Kenzuburo Oe comes to mind, as does the doomed fascist Mishima) is his incredible sense of whimsy and fun. Kafka is a charming novel, it that few of its riddles have solutions and never pretends to offer up a definite, great truth. It suggests at them-- the characters' conversations about Eichmann, Haydn, and eel all stand as wonderful examinations of ideas-- but it's a book whose rambling, tangled story and symbols are more fun than profound. I think that the village towards the end of the book represents a partial afterlife where the permanently damaged parts of people go to die, I think that recovery and redemption are major plot points, but, unlike Faulkner, I don't have to know. Murakami is a writer who, like Vonnegut, manages to be incredibly affecting and stirring without the need for grandiosity, whose works are both incredibly smart and incredibly fun. He creates worlds that obey their own logic, and it is clear that, while there are rules and laws, we will never know all of them. And, as a tourist in his world, maybe we'll have more fun if we don't.

Read: Haruki Murakami: On seeing the 100% perfect girl one beautiful April morning

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)